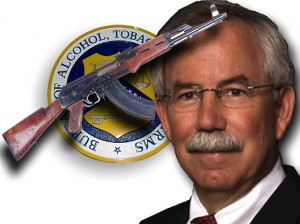

ATF Director And US Attorney Resign As Fast and Furious Gunwalking Scandals Continue

Known as “Operation Gunrunner’ and “Fast and Furious”, the program allowed straw sales of weapons to be observed and then allowed “to walk” to Mexican crime syndicates and other clients in need of high powered arms.

Dennis Burke, the U.S. Attorney for Arizona also submitted his resignation, after being interviewed by Congressional investigators behind closed doors on Aug. 18.

From CBS News:

Sources tell CBS News that the Assistant U.S. Attorney in Phoenix, Emory Hurley, who worked under Burke and helped oversee the controversial case is also expected to be transferred out of the Criminal Division into the Civil Division. Justice Department officials provided no immediate comment or confirmation of that move.

The flurry of personnel shifts come as the Inspector General continues investigating the so-called gunwalker scandal at the Justice Department and theATF.

The gunwalking scandal centered on an ATF program that allowed thousands of high-caliber weapons to knowingly be sold to so-called “straw buyers” who are suspected as middlemen for criminals. Those weapons, according to the Justice Dept., have been tied to at least 12 violent crimes in the United States, and an unknown number of violent crimes in Mexico.

Dubbed operation “Fast and Furious,” the plan was designed to gather intelligence on gun sales, but ATF agents have told CBS News and members of Congress that they were routinely ordered to back off and allow weapons to “walk” when sold.

Previously, ATF Phoenix Special Agent in Charge Bill Newell was reassigned to headquarters, and two Assistant Special Agents in Charge under Fast and Furious, George Gillett and Jim Needles, were also moved to other positions.

Vincent Cefalu, a special agent at the ATF, is interviewed on Democracy Now, and gives a detailed account of how Operation Gunrunner devolved into ‘Fast and Furious’, while ATF agents allowed military grade weapons to ‘walk’.

AMY GOODMAN: A botched operation to track the flow of guns from the United States into Mexico has prompted the resignation of the acting director of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. The U.S. attorney in Arizona, whose office was heavily involved in the program, will also step down.

Under the once-secret program, called Operation Fast and Furious, federal agents encouraged U.S. gun shops to sell thousands of weapons to middlemen for Mexican drug cartels. The program was meant to gain access to senior-level figures within Mexico’s criminal organizations. But agents lost track of as many as 2,500 guns.

Last week, the Department of Justice acknowledged to Congress that firearms connected with the ATF’s controversial sting operation were used in at least 11 violent crimes in the United States, including the slaying of a U.S. Border Patrol agent. Meanwhile, Operation Fast and Furious never led to any arrests.

The ATF’s acting director, Kenneth Melson, had recently faced pressure by Congress to resign. He’ll be replaced by the U.S. attorney in Minnesota, Todd Jones. Earlier this month, three key ATF supervisors of the heavily criticized program were promoted.

For more, we’re joined by one of the agents who helped blow the whistle on Operation Fast and Furious. Vincent Cefalu is a special agent at the BATF.

We welcome you to Democracy Now! Tell us what it is that you exposed and the significance of the head of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms resigning. He’s now being reassigned.

VINCENT CEFALU: It’s clearly significant that we’re getting some leadership. We’ve been screaming collectively across the country, the field, for new leadership for several years now. It’s a shame it had to come to this before anybody would listen. So, out of something tragic, maybe something good can come. It’s long overdue for a change in leadership, obviously.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about your own role in exposing Operation Fast and Furious? I think as people listen to the description of what it did, of government agents encouraging thousands of guns to be sold by U.S. gun shops to Mexican middlemen, to somehow get Mexican drug cartels, are rather shocked.

VINCENT CEFALU: It was an outrageous scheme, preposterous. I mean, I can’t think of enough adjectives. But I do want to be clear: there was an equal number of agents dedicated and willing to put their careers and their personal well-being on the line to come forward. I was merely, in this particular scenario, the conduit, because I had become well known for having tried to expose and correct deficiencies and ethical lapses in ATF management over the last couple years that led to this. This is not the only failure of the Bureau under our current leadership and our executives. Virtually every one of our programs have failed over the last three to four years, and we need to get this agency back on track, because it’s one of the most important agencies to public safety and the security that we have.

AMY GOODMAN: So you first complained in what, like six years ago, in 2005?

VINCENT CEFALU: In 2005, with regards to regional issues of gross mismanagement, waste, fraud and abuse, ethical lapses by the leadership of the San Francisco field division that was well documented. That sort of catapulted me into a position, because of my seniority and because I know so many people, that my phones and email started ringing off the hook, and I became aware that it was going on nationwide, that the era of reprisal and this whole draconian “do as we say, not as we do” mentality, through a lack of leadership and part-time directors and acting directors, I was in a position to try to help some of these other agents who were suffering the same sort of retaliations for doing the right thing, upholding their oath of office. And then that sort of—

AMY GOODMAN: Did you face retaliation?

VINCENT CEFALU: Oh, I’ve faced withering, horrendous retaliation for the entirety—

AMY GOODMAN: Within the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms?

VINCENT CEFALU: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: What happened to you?

VINCENT CEFALU: Absolutely. Well, over the course of it—and I’m going to try to be as specific as possible—I think there’s been two or three suspensions, three or four reprimands, five transfers in 16 months. I’ve been idled in a cage, basically in an empty office with nothing to do, for two years, terminated twice.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re currently working for the BATF?

VINCENT CEFALU: I am. I’m facing a proposal to be terminated right now. But yes, I am currently an ATF special agent. And my attorneys at Krevolin & Horst are responding to those proposals.

AMY GOODMAN: And where do you work? Do you actually work, when you’re supposedly there?

VINCENT CEFALU: I am on duty at my residence.

AMY GOODMAN: So they’re paying you not to work?

VINCENT CEFALU: Look, they’ve been doing that for two years, and denying to the OIG and the other oversight bodies that that was occurring.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Vincent Cefalu, were you one of the federal agents who were sent out to encourage these U.S. gun shops to sell thousands of weapons to middlemen for the Mexican drug cartels?

VINCENT CEFALU: No, absolutely not. Those were agents out of the—primarily, the Phoenix field division. And as we now know, the program was expanding into other field divisions, as well. You know, Senator Grassley and Chairman Issa and the committee with Ranking Member Cummings are looking into all that. But no, I was not personally involved. I was merely an advocate in—the people were scared to come forward, because they had seen nationwide what had occurred to me and others, such as Jay Dobyns and Rene Jacquez and John Dodson and other whistleblowers who came forward to do the right thing. So they used me and this website, cleanupatf.org, to get the information to the senators and congressmen to provide oversight.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain more how this worked, since also agents came to you very concerned. Take us step by step through it, what you understand. An agent walks into a gun shop and says to the gun shop owner, what?

VINCENT CEFALU: It’s not generally—I mean, this was a wide-sweeping misconception of a program from minute one. But with regards to that, the—our investigations, without disclosing any trade secrets, allow us to track people who shouldn’t be buying firearms or buying them for the wrong reasons. Generally, normally, usually, in an expeditious manner, we intercept those firearms or those people. When possible, we develop probable cause and make arrests and prosecute them. When we can’t prosecute them, we clearly intercept the guns and conduct an investigation. In this case, the agents were directed to allow the guns to continue on, minimal surveillance, not to track them to their final destination, which would have been impossible because we were withholding information from our counterparts in Mexico.

So any suggestion that our intent was to track them to their final destination and target these big cartel members is ludicrous. It couldn’t have happened, because the minute it would have gotten to the border, any of the guns would have gotten to the border, we lost contact, because we had made no arrangements, and we were secreting this information from the Mexican government. So we allowed these guns to go, continue on, in the hopes of establishing some sort of chain, or this iron pipeline, which was so far from the truth, but we were never going to be able to follow it to fruition. A junior agent, fresh out of the academy, would have been able to deduce that. So, the only way to track those guns were to find them at the crime scenes or dead bodies.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, as the New York Times reported, one straw purchaser, a middleman, bought 600 weapons.

VINCENT CEFALU: That’s outrageous. Having worked firearms trafficking for my entirety of my career, and having been solely directed at violent crime, we would never—we, collectively, as a field, as a mission-related organization, with proper leadership—ever allow that many guns to get out of our control before intervening on some level.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Vincent Cefalu. He’s a special agent at the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, has spoken out against ATF practices, including this controversial Fast and Furious program. So, let’s see. Roughly summarized, you’ve been transferred five times in 16 months, reprimanded three times, suspended two times. You’re working from home now. You’re paid—how much are you paid a year to stay home and do nothing?

VINCENT CEFALU: Somewhere in the vicinity of $150,000.

AMY GOODMAN: And yet, you continue to speak out. You just talked about dead bodies. Let’s talk about Brian Terry, the agent, Border Patrol agent, who was killed in Arizona in December. Talk about what happened to him, Vincent.

VINCENT CEFALU: We’ve had a mantra, since my time with ATF, which is coming up on 25 years, but throughout our inception. We take firearms getting in the hands of criminals extremely seriously. And there’s been a mantra that we will never let a gun walk, never let it lose our control, if we have the ability to stop it, for the very reason, the sole purpose, because we do not want to have the responsibility of a law enforcement officer, particularly, being killed at the hands of one of the guns we could have stopped. And that’s what makes Brian Terry’s death—and potentially Jaime Zapata, as well—so tragic, because one of our own suffered the ultimate sacrifice that, at least for our part, could have been prevented. You’re not going to stop criminals from getting guns ever, but in this case, we particularly facilitated the bad guys. And unfortunately, the Terry family paid the ultimate sacrifice. And I’m sorry for that part of it, that we couldn’t do more.

AMY GOODMAN: Operation Fast and Furious guns found at the crime scene.

VINCENT CEFALU: That’s correct.

AMY GOODMAN: And Zapallo sic? Who was he?

VINCENT CEFALU: Zapata, Jaime Zapata—

AMY GOODMAN: Zapata.

VINCENT CEFALU: —was an ICE agent in Mexico who was recently killed in an ambush of some sort, and I guess there’s some information or evidence, on some level, that some of the firearms may have been tied to Fast and Furious. But whether they were or not, the violence—it illustrates the violence that we’re supposed to be impacting, you know, on both sides of the border. We gave a commitment to the Mexican people that we were going to do our part, and we did just the opposite.

AMY GOODMAN: Vincent Cefalu, I wanted to talk about the Arizona U.S. attorney, Dennis Burke, who’s been removed from his involvement in this program, in Operation Fast and Furious, the significance of this, but also the fact that key three agents were actually promoted, as the head of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms was forced out. And they were supervisors, heavily criticized themselves.

VINCENT CEFALU: Oh, that action, in and of itself, with the architects of Fast and Furious being moved and protected in their current positions, pending an investigation by the U.S. Congress and the Office of the Inspector General for the Department of Justice, is just outrageous. It’s more of the same. And quite frankly, those sort of decisions are what led to Mr. Melson being recalled back to the Department of Justice and placed in another position. Clearly, until the—these—Bill Newell and George Gillett and Agent Voth, these supervisors you’re talking about, have a right to due process just like anybody else. But with the evidence that’s out there and the allegations that they have committed, clearly they should not be in leadership positions. Clearly, the taxpayers should not have had to foot the bill for these high-dollar moves back to Washington so their positions could be protected, their salaries and benefits, and hopefully take them out of the public eye, where there’s no accountability. You saw the testimony before Congress. Clearly, these people—clearly, Bill McMahon should not be in charge of our internal affairs, who’s the direct conduit for the Office of Inspector General—

AMY GOODMAN: So the people—

VINCENT CEFALU: —for this investigation.

AMY GOODMAN: The key supervisors — I’m reading from the Los Angeles Times — William McMahon, who is the ATF’s deputy director of operations in the West, where the illegal trafficking program was focused, William Newell and David Voth, both field supervisors who oversaw the program out of the agency’s Phoenix office, they have now been bumped up and promoted.

VINCENT CEFALU: Well, technically speaking, and the assistant special agent in charge, George Gillett, who was integral to this operation, as well, they’ve all been moved, lateral in most cases. So, technically, there’s not a promotion in title. However, they’re all maintaining their senior executive pay. They’re—been placed in leadership status, not demoted, not accountable.

And again, we just paid — the taxpayers being “we” — to move them into a safe zone in headquarters, where they could, you know, take the limelight off them, when there may be prosecutions coming down the road. Now, why did we pay a half-million dollars to move them before the outcome of this investigation was complete? Why are they at all involved in vetting the information that will be turned over to the OIG? How can Bill McMahon, as the deputy assistant director for this entire program, after testifying, that abysmal testimony, be the direct contact to the Office of Inspector General who’s investigating him? I’m not sure how that’s going to work out.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Republican lawmakers are saying they think the Justice Department is holding back documents and stonewalling their attempts to find out more about Operation Fast and Furious. What do you think, Vincent Cefalu?

VINCENT CEFALU: Oh, I think it’s absolutely correct. I think the Democratic lawmakers on the committee are just as frustrated. They’ve expressed it. Ranking Member Cummings is equally frustrated. And they should be. I, myself, in trying to defend my own dispute, have FOIAed my own transfer records, which resulted in the now-infamous Chairman Issa blacked-out, redacted page of my own transfer. This is not transparency, and this is not consistent with what the President’s directives for transparency have been. Hopefully that’s going to change, because at the end of the day we do work for the American people. We do—we did take an oath to the Constitution, not to Eric Holder, not to President Obama, not to Chairman Issa, not to anybody else. We’re accountable to you, to the American people, and you have a right to know what we’re doing with your money and your resources.

AMY GOODMAN: So, to be clear, the head of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, Melson, has been reassigned. Burke, the U.S. attorney in Arizona, has resigned. Is that right?

VINCENT CEFALU: That is correct. I saw the resignation letter. Kenneth Melson has been reassigned to a policy position over at main Justice. So, that is correct, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to end with the comments of the Mexican president, Felipe Calderón, who repeatedly called for the U.S. to implement stricter firearms laws. He’s accused the Americans of, quote, “irresponsibility” on arms sales. This is a comment he made last year.

PRESIDENT FELIPE CALDERÓN: [translated] The Americans began to sell arms as a voracious, ambitious industry, like the American arms industry. This often provokes conflicts in countries that are poor and less developed, such as Africa, due to the sale of arms, is in a very similar situation to that which is being lived by the Mexican people. For the arms traffickers, it’s a business to sell arms to criminals, and we need to mobilize not just public opinion against this, but unite with international public opinion to show the irresponsibility of the Americans, as much as it bothers them or hinders their political campaigns.

AMY GOODMAN: Mexican President Felipe Calderón last year. Your response, Vincent Cefalu, special agent at the BATF?

VINCENT CEFALU: Well, with all due respect to the President, he’s entitled to his opinion and his assessment. I mean, they’re—at our hands, at our agency’s mismanagement, they’ve suffered a lot in Mexico. But the more laws—we had the laws. We didn’t enforce them. Bill Newell and our leadership did not interdict those 2,000 guns. Had we, we wouldn’t be having these conversations right now. I wouldn’t be here this morning, and our agency wouldn’t be in disarray. So, you can put a thousand laws on the book. That’s not to say laws can’t be improved and tightened, or penalties. That’s Congress’s job; that’s not my job. We’re supposed to be apolitical. We don’t have a position. You give us the laws, we’ll enforce them to the best of our ability.

But in this case, we just didn’t do our job. It was a total case of malfeasance across the board, and no one chose to step up and do anything. We have senior managers saying they were aware of this. They questioned it in private briefings, in meetings. I believe Deputy Assistant Director Steve Martin said he asked, during his interview with Mr. Issa’s committees, he asked, “How long are we going to let this go on? When are we going to stop this?” He had a duty to report. He had a duty to use his authority and his position to stop it. But that’s not career-enhancing, so this whole “go along to get along” that’s brought our Bureau down has to stop. People have to start doing their jobs, and we need some accountable leadership.

AMY GOODMAN: Vincent Cefalu, I want to thank you for being with us, special agent of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, has spoken out against ATF practices, including the controversial Fast and Furious program, and has been put out to pasture as a result, if you say. He’s still working for the BATF, at home, with nothing to do. Now, the Attorney General, Eric Holder, has announced the resignation of the United States attorney in Phoenix, Dennis Burke, and the reassignment of the acting head of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, Kenneth Melson. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. Vincent Cefalu, speaking to us from Reno, Nevada.

bisbee.net

bisbee.net

WordPress AMP Plugin

20.05.2025 - 14:43:41