On the tenth anniversary of the Guantanamo indefinite detentions, Ojibwa writes about the Apache Prisoners of War. The Chiricahua Apaches were indefinitely detained as Prisoners of War, and their land was confiscated. Cochise County is named after the Chief of the Apaches, who still have a legal claim to the land that was stolen.

While the idea of “indefinite detention” of people determined to be “enemies” of the United States is currently being debated, for American Indians this is an old issue and one in which they have had a great deal of experience. In 1885, the Chiricahua Apache-men, women, and children-surrendered to the United States Army on the condition that they were to be held as prisoners for two years and then they were to be allowed to return to their own land. Instead, they spent the next 27 years as prisoners of war in prisons in Alabama, Florida, and Oklahoma.

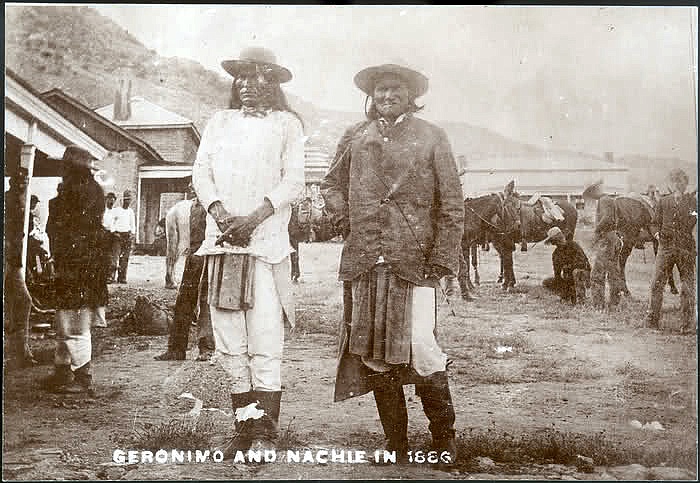

One of the leaders of the Chiricahua Apache was a warrior and medicine man known to the Americans as Geronimo. In 1876, the Chiricahua Apache settlement near Fort Apache, Arizona, had been broken up by the Americans and the people were forced to move to the San Carlos Apache Reservation. A number of Chiricahua Apache, however, did not go to San Carlos, but instead fled to the Sierra Madre Mountains in Mexico. From here, Chiricahua Apache warriors under the leadership of Juh and Geronimo raided American settlements in Arizona and New Mexico.

During the peace negotiations, Geronimo insisted that his reputation had been ruined by rumors and innuendo. He claimed that he was simply the victim of gossip and that he was not responsible for the murders and other crimes which had been attributed to him.

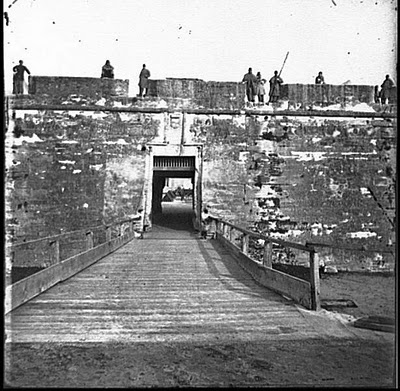

The American authorities planned to send the Chiricahua Apache to the Fort Marion Prison in St. Augustine, Florida. They were not charged with any crimes, nor did they get an opportunity to plead their case in any court of law. The United States simply held them indefinitely. While the government would claim that they were technically prisoners of war, Chiricahua Apache historians tend to characterize them as political prisoners.

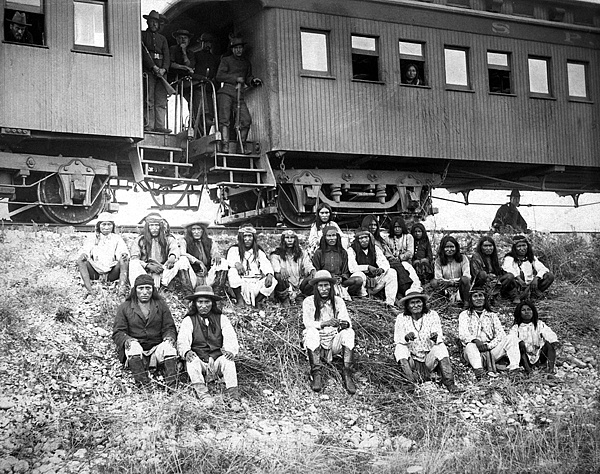

The United States Army did not track down the Chiricahua Apache in Mexico’s Sierra Madre mountains on their own: they were led to Geronimo’s camp by Apache scouts. Following the surrender negotiations, the Army disarmed the Apache scouts and imprisoned them with Geronimo’s people as prisoners of war.

Chatto and about a dozen other Chiricahua Apache who had served as scouts for the army were summoned to Washington where they met with the Secretary of the Interior. During their return trip to Arizona, their train was suddenly turned around and they were taken to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas where they were held as prisoners. The telegram ordering their incarceration read:

“I think it is the wish of the President that the Indians who came to Washington should, none of them, return to Arizona within reach of communication with those at Fort Apache until transfer to Fort Marion has been consummated.”

Following their surrender 383 men, women, and children, were taken by train from Arizona to their prison in Florida. All of the windows in the train were closed and nailed shut. They were given buckets and cans to serve as chamber pots. The train stopped frequently so that crowds would be able to see the Apache prisoners. Overall, the stench in the train cars was unbearable.

After the first 75 Apache prisoners had arrived at Fort Marion, the commander was asked how many Indians can be incarcerated at the fort. He replied that they could take only 75 more, but recommended that no more be sent because the fort was so small. The army sent a total of 502 Apaches to the fort.

After the Apaches had arrived at Fort Marion, one of the first actions of the army was to take some of the men and older boys to an island where they were left with fishing tackle and expected to catch and cook fish for themselves. The army ignored the fact that eating fish was a cultural taboo for the Apache and continued to use fish as one of the mainstays of the rations which were issued to the prisoners.

While at Fort Marion, at least two Apache warriors- Gray Lizard and Massai managed to escape and to make the 1,200 mile trek back to their homeland.

In 1894, Congress passed a special provision which allowed the Chiricahua Apache prisoners to be transferred to Indian Territory (Oklahoma). After spending eight years at Fort Marion, the Chiricahua Apache men, women, and children who were being indefinitely detained as prisoners of war were transferred to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Following their transfer, General Nelson Miles visited the prisoners and told them that this was now their permanent home.

In 1897, the leaders of the Comanche, Kiowa, and Kiowa-Apache tribes in Oklahoma proposed selling part of their reservation to the homeless Wyandot and to the Apache under the leadership of Geronimo. The Indian agent endorsed the idea, but it was stopped by Congress.

In 1897, the leaders of the Comanche, Kiowa, and Kiowa-Apache tribes in Oklahoma proposed selling part of their reservation to the homeless Wyandot and to the Apache under the leadership of Geronimo. The Indian agent endorsed the idea, but it was stopped by Congress.

While being held as a prisoner, the United States capitalized on Geronimo’s fame among non-Indians by displaying him at various events. For the United States this provided proof of the superiority of American ways. For Geronimo, it provided him with an opportunity to make a little money. In 1898, for example, Geronimo was exhibited at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exhibition in Omaha, Nebraska. Following this exhibition, he became a frequent visitor to fairs, exhibitions, and other public functions. He made money by selling pictures of him self, bows and arrows, buttons off his shirt, and even his hat.

self, bows and arrows, buttons off his shirt, and even his hat.

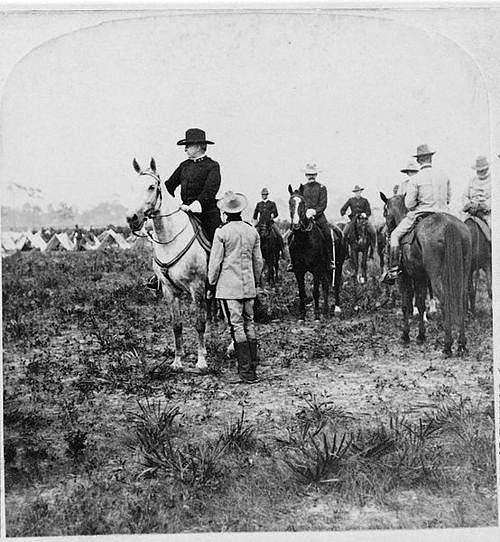

In 1905, the Indian Office provided Geronimo for the inaugural parade for President Theodore Roosevelt. Later that year the Indian Office took him to Texas where he shot a buffalo in a roundup staged by 101 Ranch Real Wild West for the National Editorial Association. Geronimo was escorted to the event by soldiers, as he was still a prisoner. The teachers who witnessed the staged buffalo hunt were unaware that Geronimo’s people were not buffalo hunters.

In 1909, Chiricahua Apache chief Geronimo died and was buried at Fort Sill.

In 1910 the United States Senate passed a bill to provide allotments to the Chiricahua Apache in Fort Sill, Oklahoma and to free them from their prisoner of war status. The measure was defeated in the House by representatives from Oklahoma.

In direct violation of promises made to the Chiricahua Apache, the School of Fire for Field Artillery was established at Fort Sill in 1910. While the Apache had been told that this would be their permanent home, the army had no intention of abandoning the post and felt that the Apache must remain prisoners. In spite of the promises made to the Apache by General Nelson Miles, when the War Department determined it was in the nation’s best interest to retain Fort Sill as an army field artillery school, they reneged on the pledges. Artillery began firing into Apache hay fields, corn fields, and grazing areas. The army notified the prisoners that shelling would not stop for livestock.

The plight of the Chiricahua Apache prisoners at Fort Sill did not go unnoticed by non-Indians. In 1911, Reverend Walter C. Roe of the Reformed Church in America describes their situation:

“The men are subject to orders; their affairs are under the direction of others; they cannot leave the reservation for more than 24 hours without permission; they cannot marry outside of their band, because no one wants to enter their condition of captivity; in fact, for the most far-sighted and intelligent among them there is no light ahead.”

Apache leader Naiche told the army:

Apache leader Naiche told the army:

“All we want is to be freed and be released as prisoners, given land and homes that we can call our own.”

In 1912 legislation was introduced in Congress which would free the Chiricahua Apache at Fort Still in Oklahoma from their prisoner of war status and relocate them on the Mescalero Apache reservation in New Mexico. The legislation was opposed by the New Mexico delegation as they wished to preserve non-Indian grazing rights on the Mescalero Reservation.

In 1913, the Chiricahua Apaches, held as prisoners of war by the Army since 1886, were transferred from Oklahoma to the Mescalero Reservation in New Mexico where they were placed under the jurisdiction of the Interior Department and given their freedom. A total of 187 Apaches went to New Mexico, while 77 remained in Oklahoma. Those who elected to stay in Oklahoma were promised allotments and rations. The following year, the government released the Chiricahua Apache in Oklahoma from their prisoner status and granted them allotments of land.

Courtesy of Native American Roots, a Forum for Native American Issues.